Updated April 2025

Hearing loss is a prevalent condition affecting millions of people worldwide. Currently, over 1.5 billion individuals—nearly 20% of the global population—experience some form of hearing loss. Of these, 430 million people live with disabling hearing loss, a number projected to exceed 700 million by 2050.

Hearing loss affects individuals across all age groups. Globally, 34 million children are affected, with 60% of these cases being preventable. On the other end of the spectrum, approximately 30% of individuals over the age of 60 experience some degree of hearing loss.

Hearing loss is typically defined by thresholds greater than 20 dB in one or both ears, making it difficult to hear conversational speech or loud sounds. The severity can range from mild to profound, and it may affect one or both ears. "Hard of hearing" refers to individuals with hearing loss ranging from mild to severe, while Deaf individuals typically experience profound hearing loss and rely on sign language as their primary mode of communication.

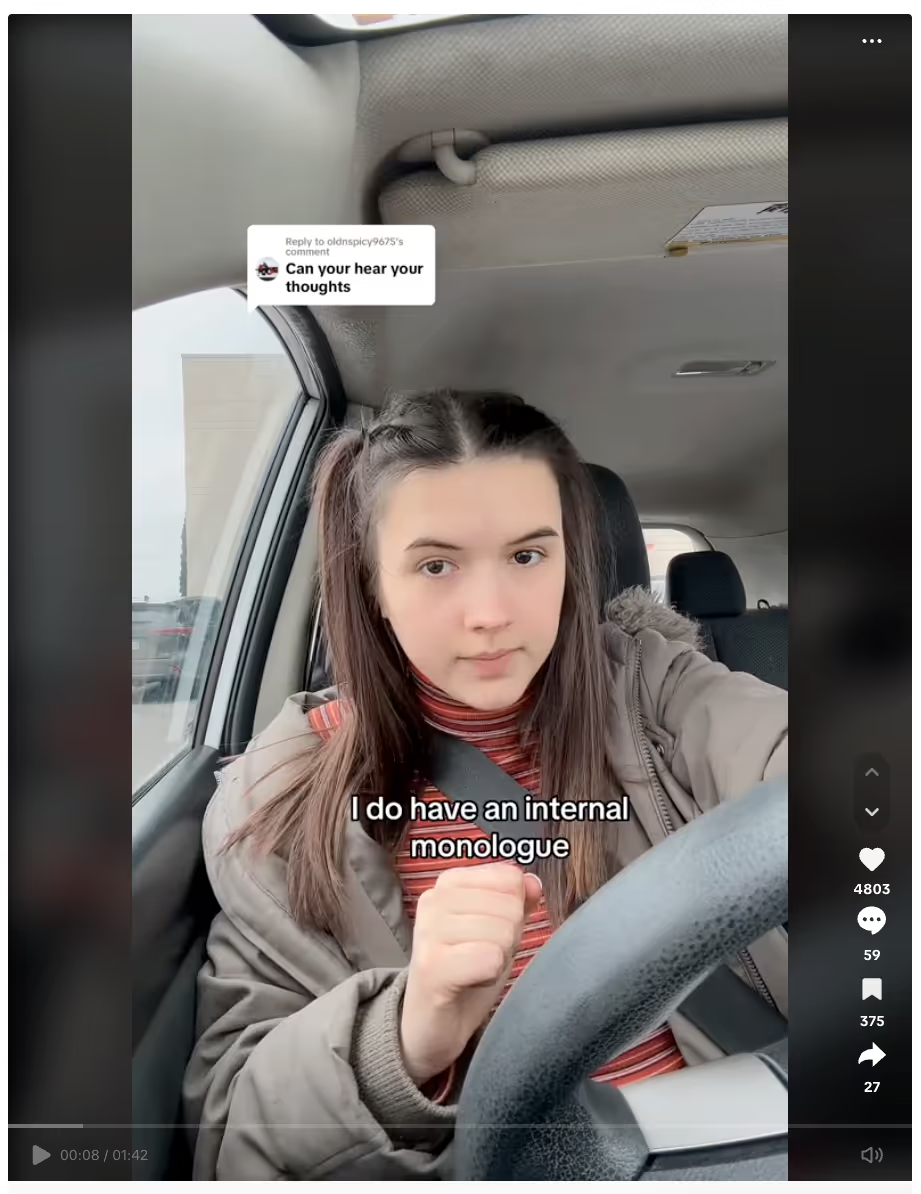

For most hearing individuals, the "inner voice" serves as a silent narration of thoughts. However, for Deaf individuals, this process differs based on their hearing experience, language exposure, and personal backgrounds. This raises an important question: if Deaf individuals do not have access to auditory language, how do they think? The following sections explore the various ways Deaf individuals experience their thoughts.

The ability to "hear" one’s own voice varies depending on when an individual lost their hearing. For instance, one individual who lost their hearing early in life reported thinking in words, but without sound. Another individual, who lost their hearing later in childhood, described "hearing" a voice in their dreams—even without relying on signs or lip movements. These personal experiences demonstrate the diversity of inner speech among Deaf individuals.

Research suggests that inner sign, similar to inner speech in hearing individuals, plays a role in short-term memory. Neuroimaging studies have shown that areas of the brain associated with inner speech are activated when signers think in ASL. This suggests that the brain uses similar neural pathways for thinking in language, regardless of modality.

The experience of an inner voice also varies depending on the extent of hearing loss and any vocal training received. Deaf individuals who were born profoundly deaf and learned only sign language typically think in ASL. However, individuals who received vocal training may occasionally think in both ASL and spoken language, imagining how spoken words sound.

The language of thought for Deaf individuals is shaped by their exposure to different languages throughout their lives. Those born Deaf or who lost their hearing early typically think primarily in ASL. However, those who have retained some hearing or received vocal training may think in both ASL and spoken language, blending the two in their thoughts.

For individuals with partial hearing, thoughts may involve a mix of spoken and signed language, depending on the degree of hearing loss and language development. Deaf individuals who have been exposed to spoken language may experience an inner voice that combines auditory memories with visual elements, such as ASL signs or finger-spelling.

Thinking in images is not unique to Deaf individuals, but it is especially common among those who have not been exposed to auditory language. Many Deaf individuals think predominantly in visual terms, shaped by the signs, objects, and scenes they encounter in their daily lives. One individual shared that their inner voice is composed of ASL signs, images, and printed words—without any auditory components. This type of thinking highlights the central role of visual stimuli in shaping the cognitive process of Deaf individuals.

The brain is highly adaptable. When hearing loss occurs, the auditory regions often reorganize to help individuals process the world without relying on sound. This process, known as neuroplasticity, enables compensation but can also lead to cognitive challenges over time.

Studies from the University of Colorado show that the brain compensates for hearing loss by activating other areas, particularly those involved in higher-level processing and decision-making. In individuals with age-related hearing loss, the auditory cortex shrinks, and other regions of the brain take over, leading to a shift in cognitive load. While this adaptation helps the brain cope, it can increase strain and contribute to cognitive decline in some cases.

The timing of hearing loss significantly influences how the brain adapts and compensates. When hearing loss occurs later in life, it often leads to changes in brain structure, particularly in the auditory cortex. This reorganization of brain cells can result in cognitive fatigue, as other areas of the brain, typically responsible for higher-level cognitive functions, are recruited to process sound. This shift increases the cognitive load on the brain, which may contribute to conditions such as dementia.

In the early stages of hearing loss, neuroplasticity allows the brain to create new connections, reassigning cells to tasks other than hearing. However, this adaptation comes with trade-offs. Once these new connections are made, the brain no longer dedicates cells to hearing, which reduces the effectiveness of future hearing aids or treatments. This makes it crucial to seek early intervention, as untreated hearing loss can have long-term impacts on brain function.

Given that age-related hearing loss is common—affecting one in three adults over the age of 60—it is essential to consider hearing screenings and early intervention. Prompt treatment can help protect cognitive function and reduce the strain on the brain. According to Dr. Anu Sharma, “Even small degrees of hearing loss can cause secondary changes in the brain, making early intervention crucial for maintaining cognitive health.”

The impact of hearing loss extends far beyond difficulty hearing sounds—it can influence mental health, social connections, and even cognitive function. Here are some important insights about hearing loss and its broader effects:

There are several misconceptions surrounding hearing loss and Deafness. Here are a few myths and the facts behind them:

The experience of an inner voice among Deaf individuals is multifaceted, shaped by the degree of hearing loss, the languages they use, and how their brains adapt. Some Deaf individuals think primarily in ASL, while others blend ASL, spoken language, and visual imagery. Regardless of the method, Deaf individuals possess a rich and complex inner world, no less dynamic than that of hearing individuals.

By better understanding how Deaf individuals think and process language, we can create a more inclusive society that values and supports the diversity of human cognition. This understanding is essential for fostering a world where everyone, regardless of hearing ability, can thrive.

InnoCaption provides real-time captioning technology making phone calls easy and accessible for the deaf and hard of hearing community. Offered at no cost to individuals with hearing loss because we are certified by the FCC. InnoCaption is the only mobile app that offers real-time captioning of phone calls through live stenographers and automated speech recognition software. The choice is yours.

InnoCaption proporciona tecnología de subtitulado en tiempo real que hace que las llamadas telefónicas sean fáciles y accesibles para la comunidad de personas sordas y con problemas de audición. Se ofrece sin coste alguno para las personas con pérdida auditiva porque estamos certificados por la FCC. InnoCaption es la única aplicación móvil que ofrece subtitulación en tiempo real de llamadas telefónicas mediante taquígrafos en directo y software de reconocimiento automático del habla. Usted elige.